The

--------------------------

Volcano

Whisperers

--------------------------

The Volcano Whisperers

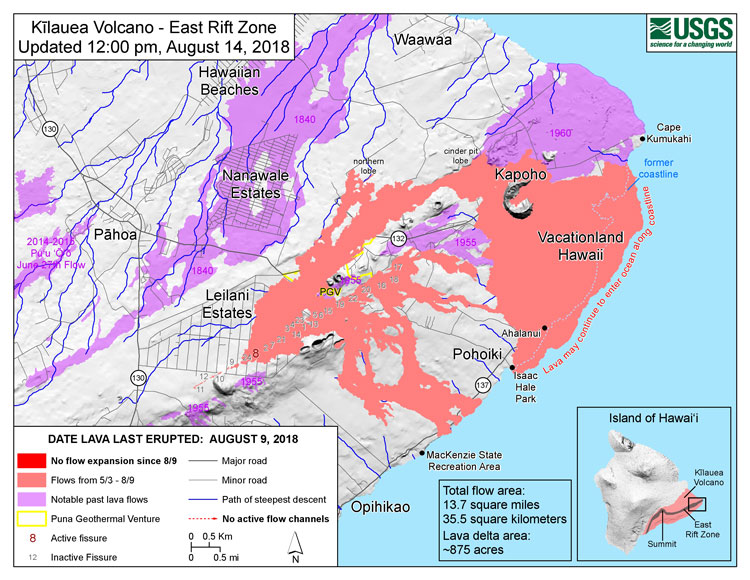

Hawaii Island's active volcano, Kilauea, had been erupting nearly continuously for 35 years. Called the "drive-in volcano" for its unique accessibility within Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, Kilauea has been a fairly predictable phenomenon, although geologists knew that eventually this would change, like everything in nature.

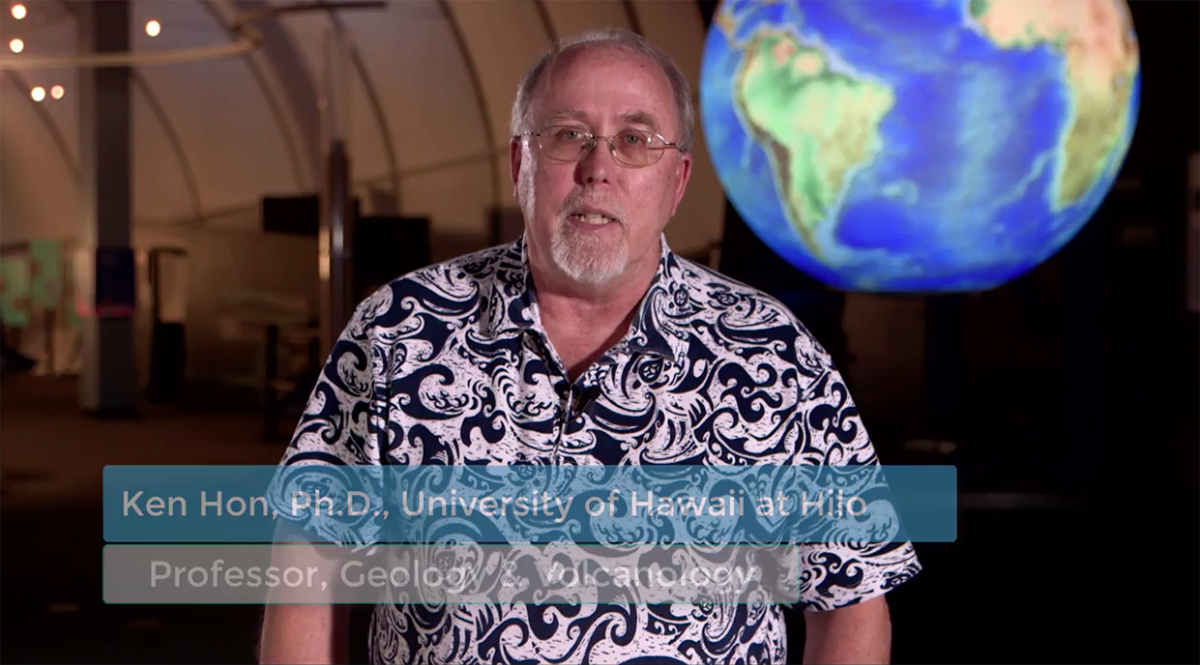

"It's like having a dragon sleeping in your yard. It could wake up any time," said Kenneth Hon, Ph.D., Professor of Geology at University of Hawaii-Hilo. On May 3 of this year, following a series of earthquakes, residents of the Leilani Subdivision in the Puna District reported lava fissures cracking roads and cutting through the forest. A new phase was underway.

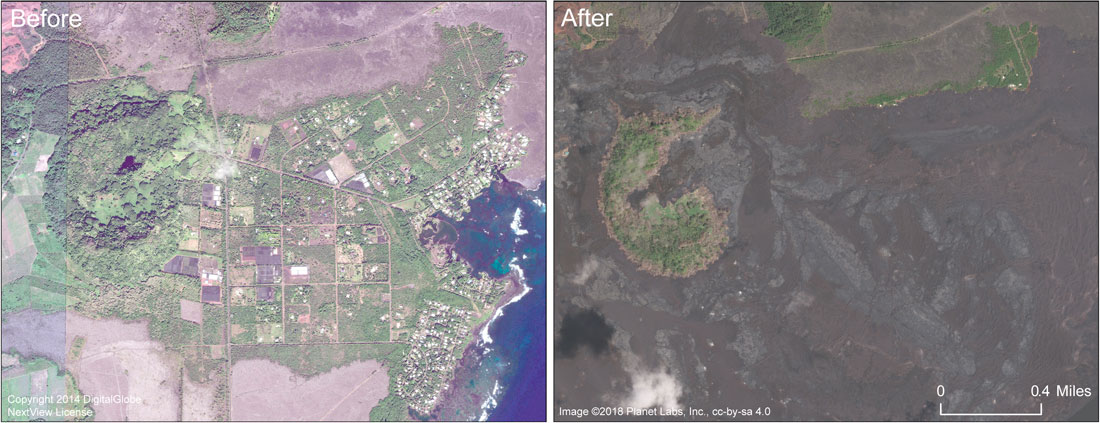

Over the next three months, the eruption continued to grow and spread, displacing area residents, as lava made its way to the ocean.

During this extraordinary event, scientists such as Kenneth Hon, Richard Hazlett and Philip Ong, helped the visitor industry "translate" the volcano's activities. This extended to residents, government agencies, news media, and individuals around the world who love Hawaii. They were able to help people understand the natural forces at work, and to make informed decisions about what actions to take next. All this while doing what they do: learning as much as they could about the eruption as quickly as possible.

"You have to be ready to mobilize," said Hon. "Put everything down, and put your whole life aside, and mobilize. When you see that kind of change, you have to have all the stuff ready to pull off the shelf and just go." Hon, with wife/geologist Cheryl Gansecki, has been researching and filming volcanoes in the Pacific, Russia, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico for many years. He is a member of the American Geophysical Union, the International Association for Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior, and the Geological Society of America. He knew this eruption was an opportunity, that was, well, hot.

Dr. Richard Hazlett remembers, "I got the call early in the morning from the Director of the Volcano Observatory, who said, ‘Get your kit ready.' So, I got my backpack, hazard gear, canteen and other things, and waited for the word. It went from an ordinary sequence of events to emergency response almost instantaneously. For months it was a matter of being flexible—prepped to drop what you're doing and go, equipped."

At 65 years old, Hazlett is an award-winning, many times published Professor Emeritus at Pomona University, Senior Editor, Oxford University Press Research Encyclopedia of Agriculture and the Environment, Affiliate Faculty Member, University of Hawaii at Hilo Department of Geology, and Associate Researcher, U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. Nevertheless, his heart still pounds when the next adventure begins.

"One of the lessons we learned had a lot to do with the social impact of an eruption in a subdivision, the diaspora of people and their response," said Hazlett. "There was not any panic. People were perhaps overly courageous... Many were quite stressed and worried about the potential loss of animals, those left behind or that ran off and couldn't be captured at evacuation... I have five friends who lost their homes."

The people in her path

On a more local level geologist Philip Ong, tour operator, wilderness trainer and now app developer, had also been keeping his finger on the pulse of the volcano. "We had some alerts in mid-April, so were primed for something to happen," he said. Ong was born in Brazil to an American mom and Chinese dad. He came to Hawaii to work for HVO, eventually forming his own business and winning Eco-Tour Operator of the Year in 2013.

"On the day of all the earthquakes (in Puna)... we were there telling people to pick up your stuff and get out," Ong said. He worked closely with fellow tour guide, social media star and local hero Ikaika Marzo, who first posted about the fissures on Facebook Live.

"On May 3, with the lava coming out of the ground, we decided we're going to set up a hub," said Ong. "The idea was, ‘We're telling people to leave, but where are they going to go?' Very shortly after, we had tents, containers for all the stuff that was donated. The Red Cross came, the Salvation Army came. We were able to tell people things like, ‘here's a path that was open about an hour ago—and here's a reasonable expectation of how long it will be open.'"

"How such a huge eruption could happen in such a developed place was shocking," said Ong. "You've seen pictures of Vesuvius, Pompei. It's not often neighborhoods get wiped out. Not what I'd planned for, not what I'd trained for, not what I prepared for."

With the help of the hub, soon dubbed Puuhonua o Puna (Puna place of refuge), residents were able to find resources and help with immediate needs. Families were fed. Animals were found and rescued. Shelter, food and support was provided, along with—perhaps most importantly—information. As the scientists shared data between the agencies, Ong and Marzo kept the local public, and a growing internet audience, informed via daily conversation and frequent Facebook Live postings—helping translate information coming from U.S. Geological Survey.

"That's why we kept it up, to fill in the gap, to help people understand what was going on so they could make decisions, and understand why decisions were being made," said Ong. "I went from explaining to visitors, to explaining to locals, to kind of a counselor," said Ong. "People were overwhelmed. We'd ask ‘what do you need - how can we help?' "I don't know. I need a place to sleep tonight.' ‘OK, here's some places you can go.'"

To their credit, Ong and Marzo had been training local tour operators, employees and interested residents in safe volcano-watching for the previous seven years. "We tried to set minimum standards, for example, no slippers, gotta have a first aid kit, gotta have a radio... It was guys like me who knew CPR and had some wilderness training. I led tours of no more than six people, and I always feared I'd find someone in serious trouble." He would tell the classes, "Our first line of defense is to train you guys so we don't have to deal with that, ever." As a result, there was a core group of people pretty well prepared to help people with the evacuations and challenging weeks ahead.

Despite what recent media reports suggest, Kilauea did not suddenly spring into action in May. It has been erupting nearly consistently from vents in the southwest and lower east rift zones since 1983. While most of Kilauea's lava flows in the 35 years have occurred in undeveloped areas in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park and nearby forest reserves, a few communities in the area were impacted including Kalapana Gardens and Royal Gardens subdivisions. In 2014, over a period of seven months, one flow came close to cutting off road access to Lower Puna. In 2016, lava slowly spilled across an unpaved portion of the Park's Chain of Craters Road and into the sea.

Shifting science

Scientists, too, had to evacuate their home at Hawaii Volcano Observatory (HVO) on May 11, when the localized earthquakes damaged its base of operations on Kilauea. Dozens of workers moved into UH-Hilo facilities. "For the guys at HVO, life is determined by the heartbeat of the volcano, and you have to respond," said Hon. "There was an amazing pressure test, especially losing HVO only 10 days into it. They went to UH classrooms and they were there 24/7."

"It's grueling; it taxes all the resources of any system," said Hon. "Normally, you operate eight hours a day, five days a week. This quadrupled the needs; we needed four times as many trained people. Imagine if 100 fires were all burning at once. For us to mobilize, we took a lot of students and trained them rapidly. Graduate students became team commanders."

Hon's wife and fellow volcanologist, Dr. Cheryl Gansecki was doing real time chemical analyses on lava samples being run to the lab almost continuously. "HVO pulled in people from all over the country—real and virtual," Hon continues. "There were at least three people in the field at all times. We had geophysicists watching on computers and interacting with people in the field."

Hazlett was in the field, close to the action, not without risk. "We always have an escape plan," he said. "We always looked over our shoulders, looking for whatever could be happening outside of our immediate focus at the moment. A threat could develop behind us, so it's like running two radars at once. Attention to what's immediately in front of you, and then this background sensitivity."

The teams were not only collecting immense amounts of data, analyzing and sharing it—they were working with rapidly changing conditions, moment by moment, at the whim of their wide-awake dragon. And they, like Ong and Marzo, used social media to communicate quickly and effectively.

"USGS had a really cool social media site," said Hon of a specifically-created site for scientists. "Lots of data and ideas could be exchanged in real time, so you didn't have to call people on the phone... It was one of the best uses of social media I've ever seen. One reason was, you could be speculative. It was not for the public, where all information has to be well thought out, well explained, etc. Here, you could toss ideas around. It was a fascinating advance."

Another fascinating advance is Ong's new app, Eruption Lens, for iOS devices. "It's a virtual reality look at eruptions in and out of the National Park," Ong said. "I've been going to whole bunch of different overlooks... and getting 360-degree images. So, if you're not able to be there, you can superimpose video images over your camera image. It's kind of like visually putting things in context based on a visual progression. ‘Oh, so this is first and then that and that. I kinda get it.' There are twelve viewpoints, all the way up to lava. The next one will have the caldera collapse and all that. I'm working furiously."